Hola and welcome to Where on Planet Earth! In case you got here by accident and are not yet a subscriber, sign up below! For more visuals on our travels follow us on IG @whereonplanetearth

Traveling the world has taught us countless positive lessons; the world is a much safer place than we are led to believe, people are kind and generous everywhere, we are all interconnected and much more alike than we think… I could go on and on. But the truth is that some of the lessons have been sobering ones; there is a lot of hate between regions and countries, there is discrimination and racism everywhere, the world is ultra nationalist. All of this leads to history being told one way or another depending on where you are and who you talk to. In essence, there are multiple narratives and many shades of history.

I think about this often because by now we are very used to hearing many versions of the same history, or hearing a single version and discovering another “hidden” one by ourselves. If we have learned anything from traveling to 73 countries, going to countless tours, visiting plenty of museums, and talking to many locals is that you have to be skeptical of everything you hear and read if your intent is to try to understand the history of a place. You have to be inquisitive, ask lots of questions, doubt any info you are given, and then do your own research. And even then, you will likely never get the full story because histories of countries are extremely complicated. Confusion is a good sign though, as almost nothing in this world is black and white. If someone is trying to convince you something is, doubt it immediately.

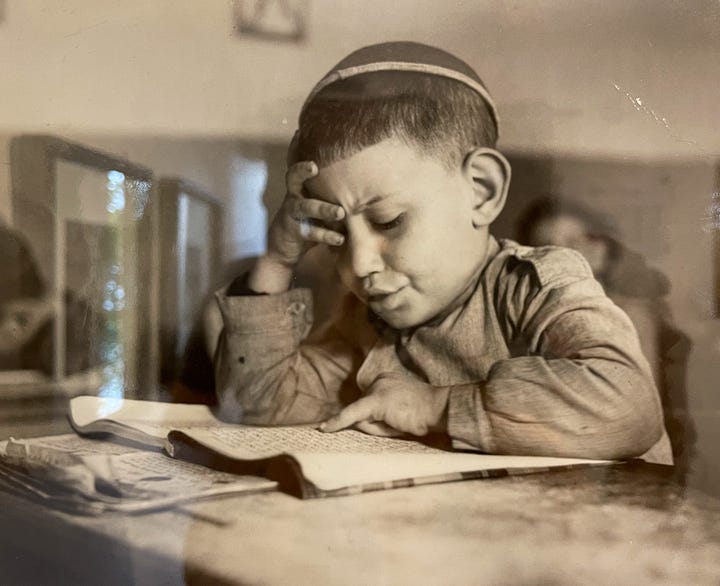

We have been in Morocco for two wonderful weeks doing many different tours with knowledgeable guides who have taught us a lot about their country. As part of these tours we were also consistently told that the very large Jewish Moroccan population simply left, migrated to Israel once that country was created in 1948 in search of better economic opportunities. While it’s true that they left, the reasons are much more complicated than that.

But before I tell you more about this complicated history, here is a disclaimer: this post is not meant to explain the full history of Moroccan Jews, because again, it’s complicated! and impossible to capture in something this short. Also, it’s important to keep in mind that Jews in Morocco actually lived better and more peacefully than Jews in Europe, for centuries! Morocco is seen today as very welcoming and acceptant of Jews, is home to the largest Jewish population in the Arab world (~3,000), and it has the only Jewish museum in the Arab world. During WWII the Moroccan king Mohammed V famously told Hitler “there are no Jewish citizens, there are no Muslims citizens, they are all Moroccans”, and true to his word Morocco’s quarter of a million Jews weren’t deported to concentration camps, in contrast to Jews in France, even though Morocco was under French (and fascist) colonial rule at that time. Just something to keep in mind.

Okay, here we go.

Jewish people began migrating to the region that is now Morocco almost two thousands years ago. But the largest migration wave didn’t happen until the end of the 15th century, when Jews were expelled from Spain and later Portugal following the Alhambra Decree (a decree signed by the Catholic Monarchs ordering the expulsion of practicing Jews). This was after many decades of intense religious persecution and killings through horrific pogroms. In the end, two thirds of the Jewish population converted to Catholicism to remain in Spain and the rest were expelled.

Side note: this is the reason both Spain and Portugal started giving citizenship to Sephardi Jews, to "compensate for shameful events in the country's past.” Basically anyone who could prove that they are the descendants of those Jews expelled from Spain because of the Alhambra Decree could receive citizenship.

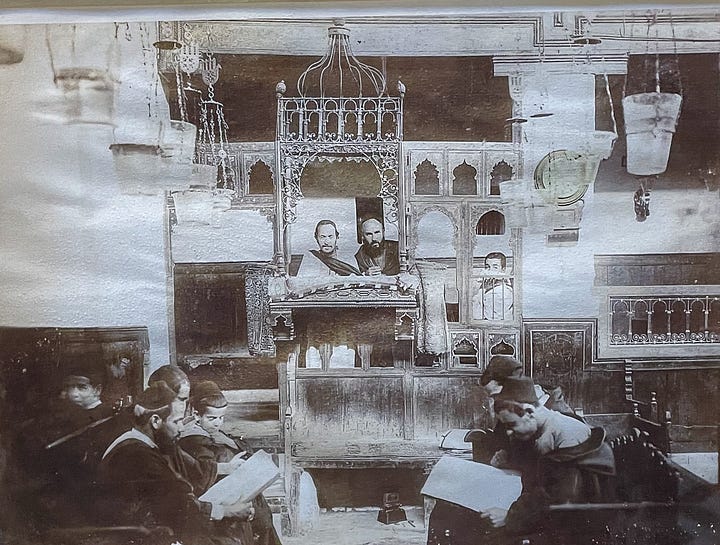

Many of these refugees came to Morocco for obvious geographical reasons, it’s so close! There is even a name for them: the Megorashim, “Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who arrived in North Africa as a result of the anti-Jewish persecutions of 1391 and the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492”. These communities settled and thrived in Morocco for hundreds of years; and they influenced the country and its culture, art, music, and architecture, which is felt even to this day.

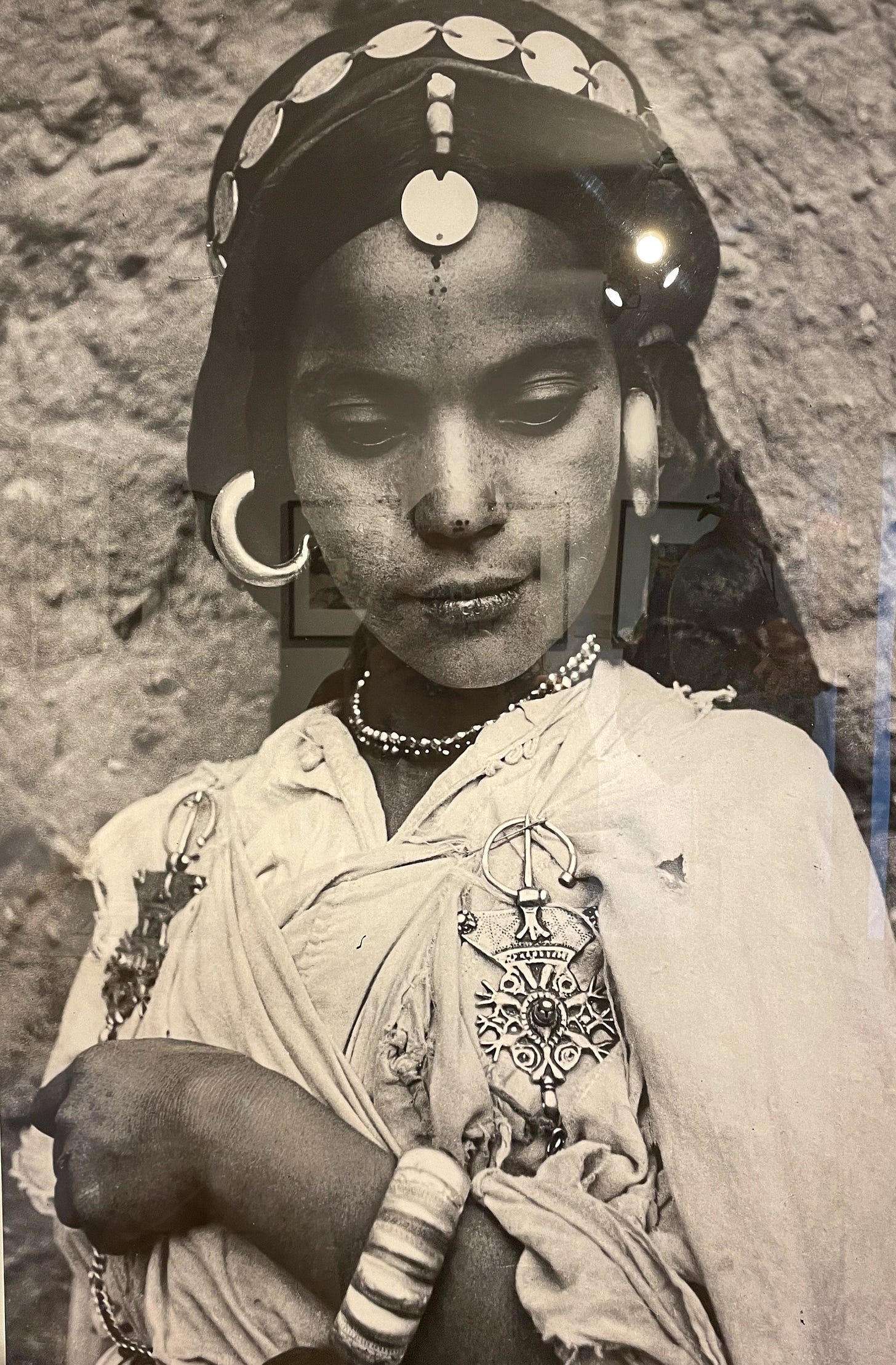

But, Moroccan Jews were also always taxed more heavily than Arabs and generally considered second class citizens. Their situation was volatile and depended greatly on which city they lived in and who was in charge at the time. There are documented persecutions, forced exiles, and general ill treatment throughout many centuries, but many Moroccan Jews also lived in relative peace and even held positions of power and influence. It was a mix bag, as so much of history is.

It wasn’t until the 20th century, when Morocco became a colony of France - or how France called it, “a French protectorate” - that things started to get progressively dangerous for the Jewish population. Colonialism is terrible for countless reasons, but an important one is that it always disturbs the social fabric, instigating and deepening divisions. In this case, French occupation upset the equilibrium between Muslims and Jews and created significant resentment from the Muslim majority towards the Jewish community. At some point, anti-French protests became anti-Jewish protests.

Things started to get even worse during WWII, when the (fascist and Nazi collaborator) French Vichy government enacted anti-Jewish laws. These laws prohibited Jews from holding public office, getting any form of credit, and basically officially designated them as a lower class. Thousands tried to flee at that time but were detained and unable to do so. The situation intensified in 1948 after the declaration of the State of Israel, when anti-Jewish riots and massacres broke out in several Moroccan cities, and anti-Jewish sentiment increased throughout the country. This event and others that followed (like pogroms in 1954) in addition to fear that Morocco's eventual independence from France would lead to more persecution and discrimination, unleashed a large-scale emigration wave.

Once Morocco became independent in 1956 Jews were granted Moroccan citizenship but with far fewer freedoms than the Muslim population, including restrictions on traveling abroad and eventually a complete prohibition of emigration if the destination was Israel (due to fear that they would strengthen the Israel fight). However, this didn’t stop Moroccan Jews from emigrating, they just continued to do so illegally. With every military conflict between Israel and the coalition of Arab states came another wave of migration.

By 1967 almost the entirety of the Moroccan Jewish population had left the country. Their departure was not solely driven by a desire to leave the land they had considered home for centuries. Rather, it was fueled by a profound sense of insecurity, social ostracism, threats, and limited prospects that they faced.

This information about the history of Moroccan Jews is not hidden; it’s not even hard to find. We didn’t come to Morocco knowing this, but tour after tour hearing the same happy story that didn’t quite seem possible, Jewish neighborhood after Jewish neighborhood now transformed into Arab communities, and synagogue after synagogue now turned into museums, made us wonder.

The story we had been told of conflict-free cohabitation and peaceful emigration was a lot more complicated than that. But it’s nicer to say - and believe - that Moroccan Jews simply left. The world, and Morocco, seems kinder if we just push a part of the reality away.

This story of Moroccan Jews is just a single example, because tales like this abound.

In Turkey and Armenia, the history of Armenians living in Turkey during the Ottoman Empire and the persecution of that community is told entirely differently depending on which country you are in.

In Spain, many people believe that colonization was a good thing for Latin America.

In Armenia and Georgia, they speak completely differently about their history as part of the Soviet Union.

In Argentina, it wasn’t until recently that as a country they started acknowledging the horrific acts of the military dictatorship.

In Armenia and Azerbaijan, the history of the land each country occupies - and who “owns” it - is told with a completely different lens.

In Chile, there are still plenty of people that consider dictator Pinochet as the best leader the country has had.

In Venezuela, Simon Bolivar is venerated as a saint for gaining independence when in fact he was also an entitled slave-owner.

In UK, many still believe the country owns all the stuff they stole from the British colonies.

In USA, people talk about how spreading democracy around the world is important but then actually do the opposite.

I am sure that the Balkans, where we are going to be spending three and a half months next, will be full of contradictions too.

I could go on and on with examples from all parts of the world.

This was a long way to say: histories are very complicated, and there are plenty of deliberate and non-deliberate blind spots people have, and sometimes that entire countries and communities have, including ours. It is important to scrutinize the narratives ingrained in us from history books, educators, parents, and society, for they often represent mere fragments of the larger picture. Question the stories you are told, including your own.

Thank you for this. Carla. These are all complicated stories, and it is important to allow them, as you have done here, to be complicated.

Appreciated the piece--another one very well done.