Yugo-nostalgia is real, and I get it

Journal Post #35: September 3rd 2023, Ljubljana Slovenia

Hola and welcome to Where on Planet Earth! In case you got here by accident and are not yet a subscriber, sign up below! For more visuals on our travels follow us on IG @whereonplanetearth

As we're nearing the end of our three-and-a-half-month road trip in the Balkans, I can't help but reflect on all that we've discovered about the region. One of the most intriguing aspects of our journey has been delving into the story of Yugoslavia, and understanding how in many ways the union and what it represented is still present in the hearts and minds of many to this day.

By now we have spent time in *all* ex-Yugoslav countries: Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kosovo, Serbia, and North Macedonia. The one thing that has been a constant throughout all of them? Yugo-nostalgia. Or rather, Tito-nostalgia, because the Yugoslavia they long for is the one under Tito, not what came after. But let’s keep it simple.

“Yugo-nostalgia refers to an emotional longing for a time past when the splintered states were a part of one country. It refers to an emotional attachment to both subjective and objectively desirable aspects of Yugoslavia, often described as economic security, sense of solidarity, socialist ideology, multiculturalism, customs and traditions, and a more rewarding way of life.”

Before our travels through all these ex-Yugoslav countries we expected there would be some people who looked back at the days under the socialist republic with a sigh and mutter under their breath “those good old days”. But we didn’t expect a lot people to feel this way. We were wrong.

In some ex-Yugoslav countries this feeling is a lot more pronounced that in others - in Serbia versus Croatia, for instance - but without fail it has been present in all. The reality is that lots and lots of people miss Yugoslavia, particularly those who actually lived through the years under the union, but also many that didn’t.

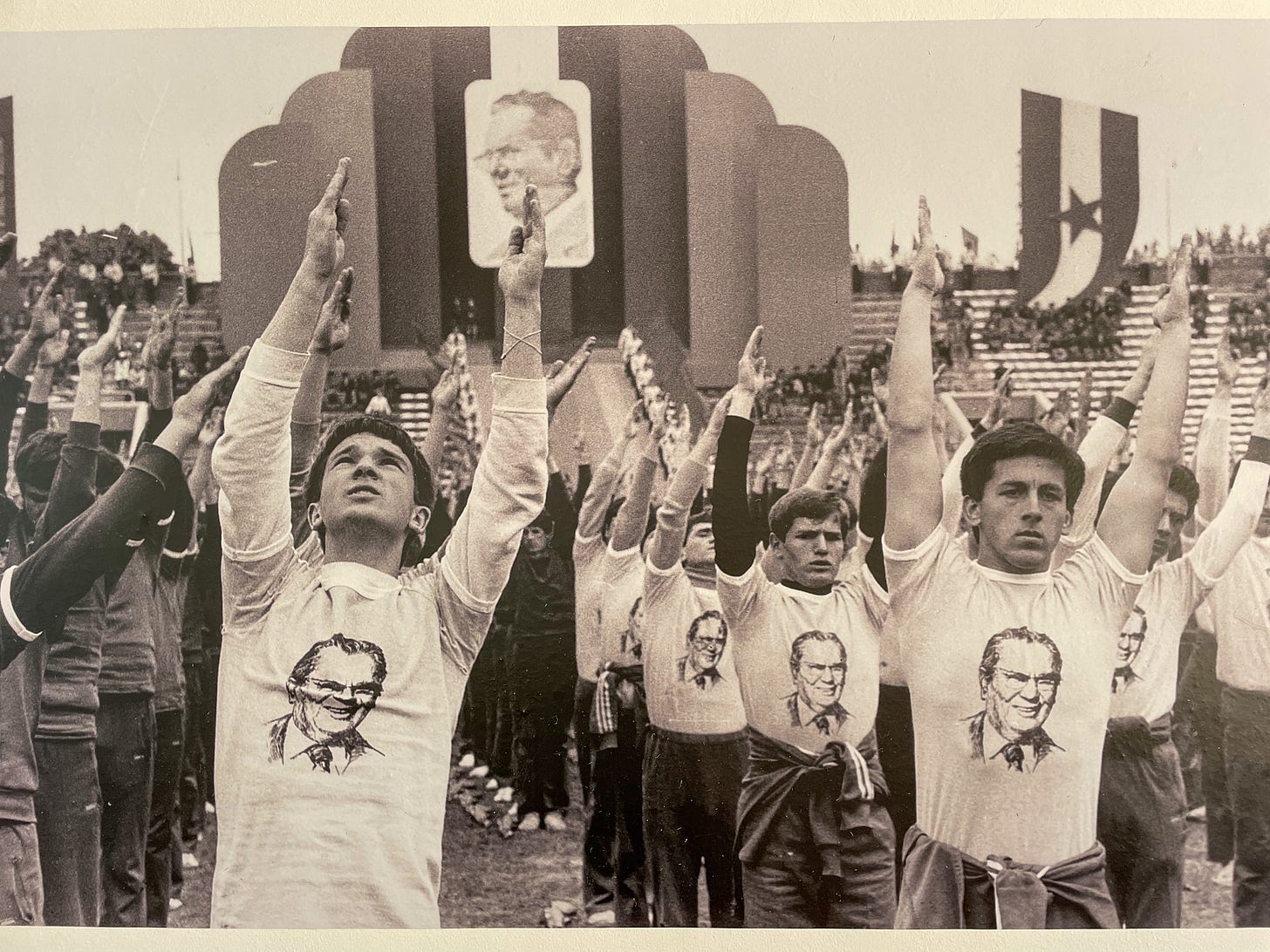

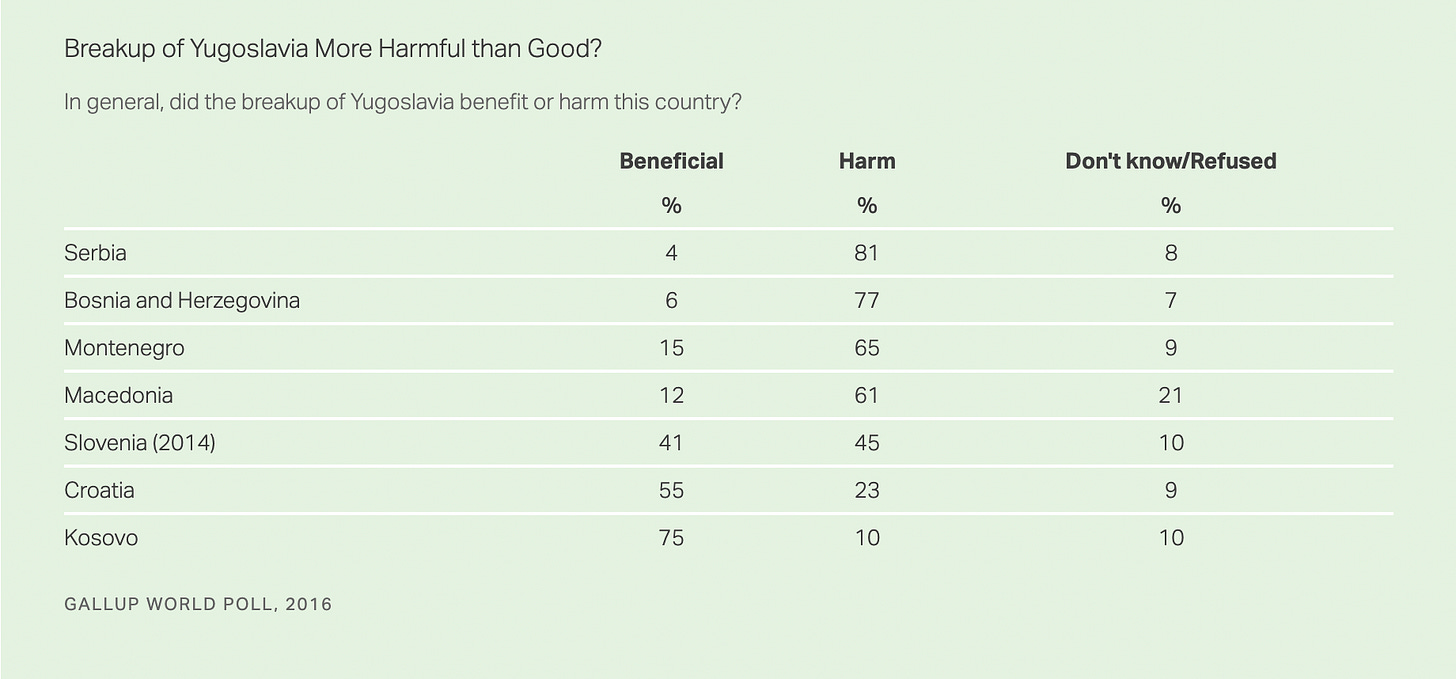

A Gallup Poll conducted in 2016 found that more than 80% of Serbians see the breakup as hurting their country. Yugoslavia was, after-all, majority Serb, so the nostalgia there seems to be in overdrive. Even to this day, on Tito’s birthday, many visit his fancy mausoleum in Belgrade to pay tribute. Side note: Tito’s funeral is, to this day, one of the world’s largest ever state funerals, attended by delegations from most of the world. Many of our tour guides all over ex-Yugoslavia told us that when Tito died they cried, no because it was politically appropriate, but because they were fond of him.

But, even in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the country that endured the most horrific of the separation wars, almost 80% of the population still hold deep affection regarding Yugoslavia. Maybe it is exactly because of how bad things ended, how bad things continue to be, that they long to return to a more united country.

In Croatia and Slovenia people are more likely to perceive the collapse of Yugoslavia as beneficial, specially the younger generations. This is not surprising, as the two countries were historically the richest in Yugoslavia and today are the only ones that are part of the European Union. Basically, they are much better off economically and politically than the rest. Our (young) tour guides in those countries told us that people live much better today that they did before they joined the EU, but not necessarily better than when their countries were part of Yugoslavia. A big portion of the older generations still consider Yugoslavia the “good old days”.

Shockingly, we also found Yugo-nostalgia in Kosovo, though it’s important to note that feeling is specific to when Tito was in charge, because what came afterwards for Kosovo was a long, bloody, and recent fight for independence. So, unsurprisingly, that Gallup poll I mentioned before found that most Kosovans see the ultimate breakup in a positive light.

Still, all the Kosovans we spoke to told us that under Tito there was peace and unity, everyone had jobs, people lived well; now Kosovo is small and struggling, with high corruption and unemployment levels, in a limbo, unrecognized by a large part of the world. For more on Kosovo’s story check out this previous post.

My point is that Yugo-nostalgia is present everywhere, even in the countries you would expect it the least.

As a Venezuelan who fled a “communist” regime with many parallels with past regimes across the Balkan regions, it has been specially enlightening to travel through the region. We are all fed different narratives about the good and the evil in this world, so depending on where you are from and where you live, you hold certain believes about communism. Think for a minute about what you associate with it. Is it shortages and poverty, is it education and health care, is it control and populism, is it equality and prosperity, is it a cult to a personality or a benevolent leader?

The truth is that communism can be all of those things and many more. One thing about traveling is that, as long as you’ll let it, it will help you expand whatever narrative you have in your head about anything. Specially the narratives you hold tightly.

But let’s rewind.

Yugoslavia was first born as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, following the end of the First World War in 1918, when four major empires - Ottoman, Russian, Austro-Hungary, and German - disintegrated and opened up space for other unions. Not long after, it officially got a re-brand as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the land of the South Slavs, and during the inter-war period it was, as many other kingdoms, ruled by dynasties that eventually fled as the Axis powers invaded their countries prior to World War II.

The Second World War in Yugoslavia was messy and bloody. The country was split among Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria, as well as internal fascists regimes such as the Croatian Ustaše. An important and effective resistance movement also sprung, the Yugoslav Partisans, led by no other than Tito, who would become the leader of the new Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia right after the war.

Although from afar it’s easy to paint all countries in communist Eastern Europe - the “Eastern Block” - with the same brush, the truth is that Yugoslavia was far from the same.

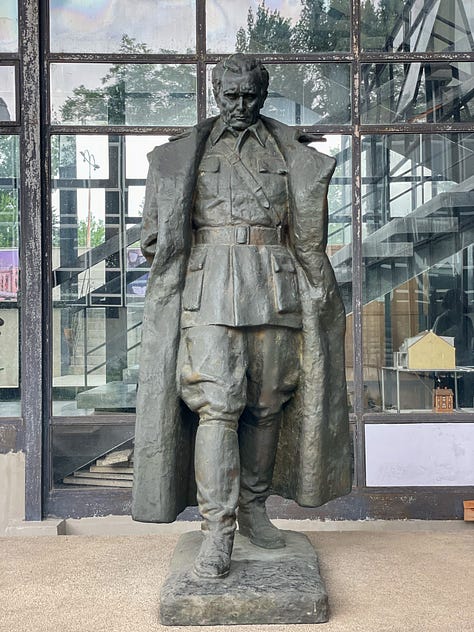

Although initially aligned with the Soviet Union, Tito bravely broke up with Stalin early on. After all, his partisan army was the one who liberated Yugoslavia from the Nazis, not the Soviet army, so he owed them nothing. This decision proved decisive in the future of Yugoslavia. He was a skilled diplomat and founded the non-aligned movement, an alliance of countries that didn’t want to formally align with the East-West/Soviet-American divide. This put Yugoslavia in a very unique position as a sort of broker between the two major power blocks.

Side note: The non-aligned countries came to be referred to as the “third-world”, the Eastern Block as the “second-world” and the Western Block as the “first-world”. These terms were a political grouping, not an economic one, but because many of the countries in the “third-world” were economically poor and non-industrialized, it became linked to the colloquial term most known today.

The non aligned movement was very meaningful during the Cold War and made Tito an extremely popular politician. By then Stalin had died, the new Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev stablished relationships with Tito once again, and the US, wanting to avoid Yugoslavia joining the Eastern Block, kept Tito happy at all costs. Let’s just say Tito was in a good position.

Even more importantly, at that point Yugoslavia was the fastest growing socialist economy in the post-WWII era and one of the fastest growing countries in Europe during the 1950s and 1960s. Tito heavily industrialized the country, built hundreds of factories, and created millions of jobs. There were no major social disparities, education and health services were available to everybody. Tito prioritized education and gender equality. There was impressive economic growth and vast improvements in the standards of living during his 30 years in power. The undeniable fact is that Yugoslavia was not communist Albania, or Romania, or Bulgaria, or even the Soviet Union. Yugoslavia was prosperous, equal, and open.

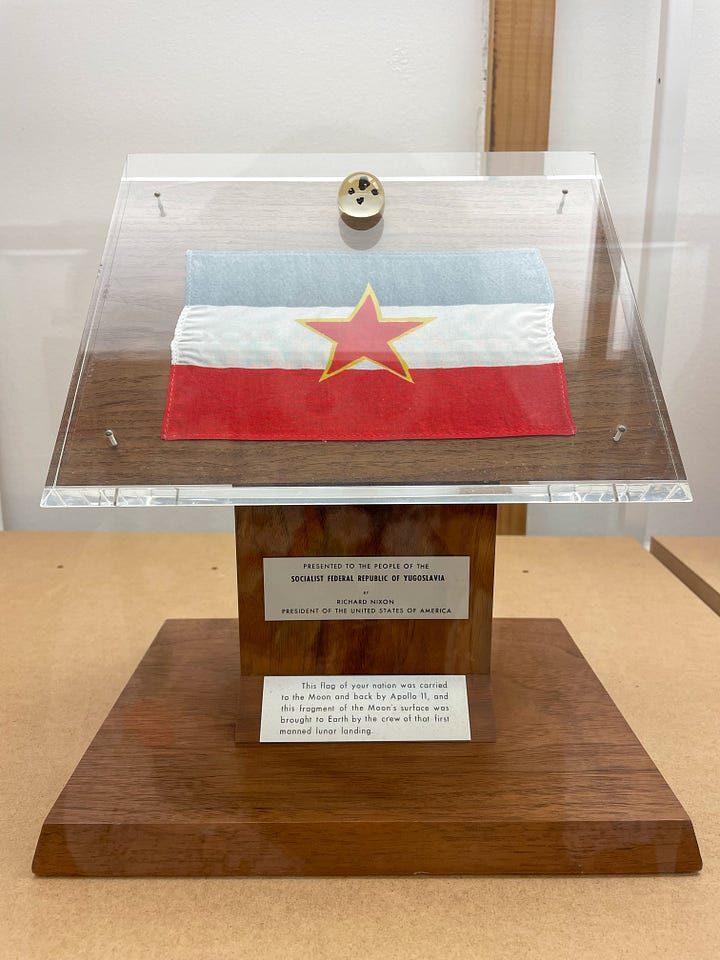

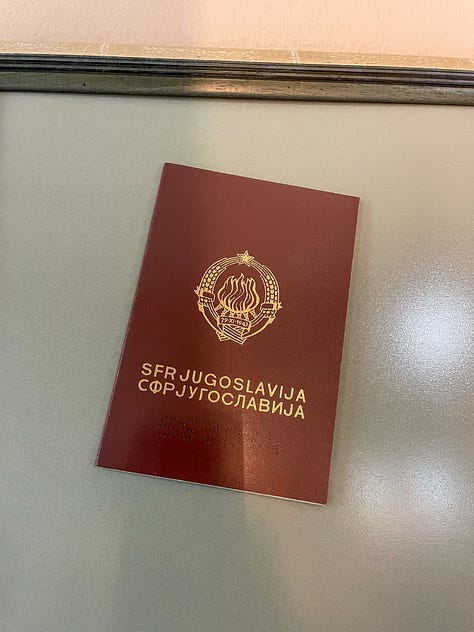

A Yugoslav passport was an excellent passport to have, as it was one of the few that allowed someone to travel freely through both the East and the West. In contrast, nowadays unless you are Croatian or Slovenian (and part of the EU), you need a visa to enter many countries around the world. This is a fact that many are quick to point out when talking about the subject.

Perhaps most crucially, Tito preached “unity and brotherhood”, a peace & love philosophy that was celebrated and embraced by Yugoslavs. “We were all Yugoslavs, and we used to live in peace” is a common phrase we heard throughout our travels. Given all the wars that came after the dissolution of the state, and all the hate present to this day, it’s not hard to understand this sentiment.

We have met many people that have parents and grandparents who were from different parts of Yugoslavia; ethnically different, yet Yugoslavian in the end. A grandmother from Slovenia, a mother from Montenegro, a grandfather from Bosnia-Herzegovina, a father from Croatia. “It was a different time, nowadays you will not find this unity anywhere”, they told us. And sadly, this is true, as most countries around the region are ethnically homogenous, and those that aren’t are extremely segregated.

But, although Yugoslavia was a prosperous society, free in many ways, equal in most, and open to the world, it was certainly not democratic. Tito was a dictator, and although not a truly malevolent one, he suffered from the maladies of all dictators. He suppressed freedom of speech, persecuted political dissidents, and perhaps most damaging, he instilled an intense cult to his personality. As a tour guide in Croatia told us, “there was no Yugoslavia without Tito”.

Tito died in 1980 when the union was already struggling, but his death accelerated the collapse. Yugoslavia had become very indebted, Western economies went into a recession which decreased demand from Yugoslav imports and this fed the already large debt problem. What followed was what set the stage to the breakup; hyperinflation, shortages, high unemployment, and the collapse of social programs. All of this in addition to Serb nationalist Slobodan Milošević coming to power and pushing a “Greater Serbia” agenda was a recipe for disaster. Skeletons started to come out of the closet; basically all the ethnic tensions that had been swept under the rug during the years under Tito came to light in full force, and the Yugoslav wars erupted.

What followed was a series of horrific conflicts plagued with war crimes including the Bosnian genocide, and which resulted in the death of 140,000 people and in a major refugee and humanitarian crisis of millions of displaced people. (For more on that check some of my previous posts, like this one about what happened in Bosnia-Herzegovina).

Ex-Yugoslav states suffered greatly from the breakdown, and not only due to the lost of lives and general trauma, but there was also huge economic decline, a staggering brain-drain as many people left to Western Europe, and high levels of corruption and nepotism that are still present in most of the region to this day. Even those countries that have successfully joined the EU bloc, although immensely better economically that the rest, also struggle with some of these conditions.

After traveling extensively through the region and talking to many locals, it’s easy to understand why many look back nostalgically at Yugoslavia and the decades under Tito. Obviously the union didn’t work, it collapsed dramatically and shamefully, but that doesn’t mean there is nothing worth salvaging from it, worth learning from.

No political system is perfect, and it would do societies good to free themselves from the rigid dichotomy of labeling one system as inherently superior to another. There is no one-size-fits-all system of governance that is universally "good" or "bad." By recognizing that no political or economic model is perfect, we can foster a more open and nuanced dialogue about the complex challenges we are facing today.

As we say goodbye to the Balkans and their multifaceted history, I will strive to always carry with me the lesson that the world is a nuanced place, that things are not always what they seem, and that I should always question my tightly held believes. I hope you do too.

Look back into the future! And see the paradise!

It is the moment of the construction of a collective idea of economic redistribution.

It is the moment of imagining the importance of one's own defense.

It is the moment of the idea of trust and non-trust.

It is a question of how to enter into dialogue with different economic ideological views.

How to have the potency to create the moment of resonance.

It is the story of a state that embraced socialism and established a nonaligned movement with countries in Africa, America, Asia and Europe.

A state that wanted to practice a form of free market economy under socialism.

And it's the state of my childhood.

We live in a not too big but perfect flat, with lots of light on both sides of the flat, with lots of green between and around the buildings, next to the boulevard and the river.

We studied Latin for a week, and Cyrillic for a week.

We eat a lot of vegetables that our mothers bought after their work at the main market in town.

In winter, we enjoy the tastiest mandarines and oranges coming from the south.

In winter we visited workers’ hotels in the mountains. And the summers were mainly reserved for the seaside.

You can meet children and adults from different Yugoslavian cities, but also from Germany, West and East, from Italy, Hungary, Portugal, Czechoslovakia, Spain, Poland, France etc. It is a time of meeting, relaxation and of course swimming.

Some guests stayed in local guesthouses, while others were residents of workers' hotels, or other types of hotels. Some owned summer houses.

Many of them were workers, all of them were workers. Some had more decisions to make, or rather, they were allowed to make decisions. They were mostly the ones with more education. And some were politically active.

- An excerpt from an exposition in Sarajevo titled “Fragmented Memories”

Where are we now?

A couple of days ago we arrived to the capital of Slovenia, Ljubljana! And wow, what a cute little city this is, I am in love with it! It’s colorful, it’s cultural, there is a river and a castle, lots of green, and fun people. Culturally, it feels quite distinct from the rest of the Balkans and also ex-Yugoslav countries, but the more we learn about its history the more this makes sense. Check out IG stories for more on this place!

As always excellent article. Very informative, interesting, and very well written. The history of Yugoslavia is fascinating and very complex. I enjoy very much reading it. Thank you for taking the time to enlightening us with the history of this interesting area of the word.

I loved to learn about Yugo-nostalgia . You make a great effort to let us know the vision of the residents of each city you visited that are part of the ex-Yugoslavia . You show us how hate causes divisions, rejection, death and trauma . Unfortunately we can see every day that the slogan

" Brotherhood and Unity" does not exist in many families .